The Top Takeaways From the 2021 ONC Annual Meeting: Actionable Data as the Great Equalizer

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) held its first fully virtual annual meeting last month with a focus on utilizing healthcare information technology and data to strengthen the United States healthcare system, address patient needs, and improve outcomes.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) – the entity over both the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) – and ONC have successfully aligned priorities according to their strategic plan for 2018-2022. [1] Included in this plan are the following goals:

- Reform, strengthen, and modernize the nation’s healthcare system.

- Protect the health of Americans where they live, learn, work, and play.

- Strengthen the economic and social well-being of Americans across the lifespan.

- Foster sound, sustained advances in the sciences.

- Promote effective and efficient management and stewardship.

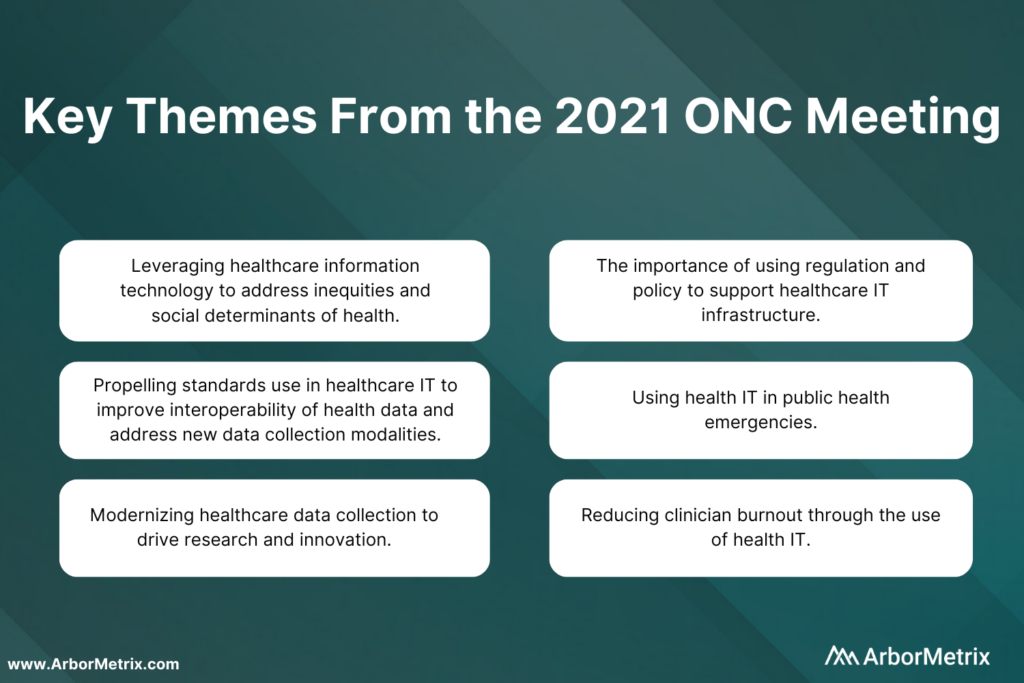

This year’s conference sought to fine tune national priorities, viewing them through the lens of COVID-19 and health inequality. The conference addressed HHS goals through the following six themes:

- Leveraging healthcare information technology to address inequities and social determinants of health.

- Propelling standards use in healthcare IT to improve interoperability of health data and address new data collection modalities.

- Modernizing healthcare data collection to drive research and innovation.

- The importance of using regulation and policy to support healthcare IT infrastructure.

- Using health IT in public health emergencies.

- Reducing clinician burden through the use of health IT.

Addressing some of the greatest challenges in health means using the most innovative technology to advance care and improve outcomes.

Addressing some of the greatest challenges in health means using the most innovative technology to advance care and improve outcomes.

While the current health IT ecosystem is surrounded by complexity and compartmentalization, new standards and technologies are creating a solid backbone to unlock greater potential impact. Organizations such as medical specialty societies can bring together diverse healthcare stakeholders to use technology and data science to collect and analyze data and advance health.

This work becomes increasingly more efficient and valuable when it is supported by technology that is aligned with the innovative standards showcased by the ONC.

Leveraging Healthcare Information Technology and Using Social Determinants of Health Data to Address Inequities

The adage that “you can’t fix what you don’t measure,” is crucial to health information technology’s role in fixing social inequity in healthcare.

Social data is exceedingly responsible for health outcomes and healthfulness. Research has shown that genetics are accountable for approximately 20 to 30% of health outcomes and medical care attributable to about 10 to 20%. This leaves roughly 70% of health outcomes attributable to behavior and social determinants of health. [2]

A person’s ZIP code is the most dominant factor in determining health. It determines access to care, access to fresh and healthy food, environmental risk, and it ultimately determines life expectancy. Now, it also means having access to information through technological innovations such as broadband internet. This has been magnified during the COVID-19 pandemic, with at-risk populations unable to access appropriate information to get the care they need.

Currently, there is a divide between health data and community needs. Until now, health information technology has disregarded its role in perpetuating systemic inequality. Often social data such as class, race, rurality, and language are missing from the electronic health record (EHRs). These data have been either not measured correctly or ignored, contributing to adverse health outcomes in poor, rural, and minority communities.

Unreliable sources of social data coupled with the lack of centralization and standardization of data constrain accuracy. This leads to underserving vulnerable populations. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the current social justice movement is creating a paradigm shift in the way race, class, and health are being examined and addressed.

Healthcare information technology has the ability to set the stage for creating an equitable health environment and can do so in four key focus areas:

- Incorporating standards through FHIR and nonproprietary open APIs.

- IT infrastructure through health information exchanges and widespread broadband access.

- Public health policy and funding for digital transformation and interoperability.

- Implementation of practices to promote health equity.

Promoting the collection and use of social data and using it to predict and rectify adverse health outcomes are necessary to drive change.

Historically, we have looked to electronic health records to be the primary information source for health data. These systems are transactional in nature and do not serve as the complex fusion network of data needed to address complex societal problems.

Moving forward, data must be pulled dynamically from different sources to adeptly address changing social needs. Healthcare IT can both challenge and change health inequity through thoughtful collection of data beyond the electronic health record. Data collection systems should incorporate “heath equity by design,” where mechanisms to achieve equity are engineered into systems for collecting and transforming health information.

Ultimately, the health consumer must be central to all innovation in health information technology. Social health information exchange can leverage existing infrastructure and integrate social determinants of health tools and applications to make social health data both available and interoperable. Funding for digital transformation, state block grants for interoperability, federal information consent privacy rules that are aligned with the needs of vulnerable populations are all necessary for achieving health equity by design.

Using Health IT in Public Health Emergencies

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the fragility of our healthcare system and has forced all aspects of healthcare, including health information technology, to revolutionize under duress. The past year has pointed out our lack of a standard, scalable case-based surveillance system that allows us to adapt to new widespread threats such as COVID-19.

Currently, electronic health records do not have the capability to incorporate data from alternate data sources such as pathogen diagnostics systems. This was a hindrance in surveillance for COVID-19.

Relying primarily on the EHR for health data limits our ability to respond to threats with agility. The pandemic has taught us that much of healthcare takes place in nontraditional spaces, and our information systems must adapt to this.

COVID-19 testing and vaccination occurs in a myriad of facilities outside of traditional healthcare spaces and we miss out on valuable data because we do not have the ability to collect information from these sources. Furthermore, people who are treated in these nontraditional spaces are typically people who suffer most from health inequities.

Propelling Standards Use in Healthcare IT to Improve Interoperability of Health Data and Address New Data Collection Modalities

The 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act) was initially set to go in effect in 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic took precedence and has delayed implementation until now. This groundbreaking regulation provides an opportunity to demystify myths surrounding interoperability and make data liquidity a priority within healthcare.

In a Stanford poll of primary care physicians, 67% indicated that they would like to see interoperability and system-wide information sharing be addressed as the most pressing healthcare issue we face in the next decade. [3]

Significant challenges lie in making health data completely interoperable. While we may focus on the creation of electronic data standards, the adoption of electronic modalities of collecting and transferring data have not reached complete saturation. Standards must incorporate all modalities and address settings where there is not wide adoption of EHRs such as in rural settings. While there is emphasis on electronic data collection, standards should be applicable to analog forms of data collection, as well.

Integration of social determinants of health data, device and mobile data, and traditional patient data from EHRs is fundamental to propelling our healthcare system into the future. Without integration, there is significant financial and human life cost to patients in the way of lack of access to care, needless repeated diagnostic care and inappropriate care. Standards will promote integration and bi-directional data exchange, allowing a deeper understanding of the continuum of patient care.

Modernizing Healthcare Data Collection to Drive Research and Innovation

Electronic health record systems primarily serve as a container for health data, rather than a tool for improving health and healthcare.

All levels of healthcare, including local and national levels, struggle to obtain timely, accurate, and actionable data from electronic health records. The current structure for data collection and exchange requires clinicians to spend less time with patients and more time interfacing with electronic systems that were not purpose-built, which results in omissions and errors. The structure is not scalable without significant resources and effort.

This mismatch between need and function fosters delays and a loss of data precision, a loss of trust amongst providers, and creates an unsustainable system at increased cost. Current healthcare data infrastructure is reactive, siloed and inefficient. To respond to future threats, the infrastructure must be transformed into a system that is predictive, agile, and focused on sharing and understanding timely data and resources.

To overcome these barriers, health agencies such as the CDC and other partners are looking to utilize API gateways to support streamlined, coordinated, and interoperable public health reporting. Ongoing modernization includes leveraging cutting-edge analytics and data visualization capabilities to seamlessly integrate data from disparate sources.

Health data is increasingly being generated by sources other than patient visits and electronic health records. With the advent of personal health devices such as continuous glucose monitors and fitness wearables, patients are increasingly creating and monitoring their own health data. By 2025, there will be over 180 billion gigabytes of sensor data generated by Internet of Things devices, much of this data related to health and fitness. [4, 5]

As the technology for these devices matures, this data has far-reaching implications for healthcare, including remotely monitored condition management, chronic condition self-management, faster diagnosis, earlier interventions and medication compliance. Incorporation of sensor data in healthcare can potentially streamline resource use, increase quality and lower cost.

The COVID-19 pandemic created an increase in telehealth visits. Having remote access to diagnostic sensor data will transform the utility of telehealth, creating the ability to easily provide care in rural and nontraditional settings.

Currently, most sensor data do not adhere to standards-based protocols and unless the data is unified and interoperable, it will continue to create vertical silos which creates superfluous complexity in data flow. [5] Sensor data will be of limited utility and is unlikely to reach the saturation needed to be viable unless standards-based interoperability is built in from the start.

While technological innovation is important to modernizing healthcare data collection, it cannot be done without a robust public health workforce. In addition to making data interoperable, we must focus on reskilling and retaining a vigorous data science workforce including public health informaticists to carry out 21st Century public health work. This requires significant funding and investment into public health human resources.

The Importance of Using Regulation and Policy to Support Healthcare IT Infrastructure

Policy and regulation can be drivers of public health change at the local, state, and national level.

The Cures Act lowers the barrier for data liquidity through information blocking provisions, availability of nonproprietary APIs, support of bi-directional data exchange for data flow amongst multiple entities, and transparency for patients through the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA). TEFCA outlines conditions to be met to promote secure exchange between providers, health information networks (HINs), and patients. This puts the patient at the center of healthcare IT and promotes ownership and patient management of data.

Required implementation of secure, standards-based application programming interfaces (APIs) by providers will make patient data readily available to aid in making timely decisions about patient care. This can be leveraged to power clinical decision support tools such as CDS Hooks that work in real-time to support clinician workflow.

The Information blocking provision in the 21st Century Cures Act prohibits health IT developers of certified health IT, health information networks, health information exchanges, and health care providers from engaging in practices that interfere with access, exchange or use of electronic health information. These provisions promote patient-centered care and allow patients greater access to their own health data and prohibits providers and health information technology developers from holding data ransom for financial or personal gain.

Lastly, new office and outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) coding and guideline changes improve clinician workflow, infrastructure and ultimately patient experience by reducing administrative burden of documentation. [6] The streamlining of coding and documentation requirements for evaluation and management codes and elimination of “documentation for the sake of documentation” will lead to payment for patient visits being resource-based rather than time-based.

Ultimately, policy is necessary to drive standard, widespread change across healthcare. Regulation has the power to drive data integration, a fundamental need to the health of this country. Proprietary systems have reason to remain siloed to protect economic interests and are unlikely to change unless forced.

While there have been significant improvements with the advent of the Cures Act and other guideline changes, additional work is needed to create national frameworks and best practices for choosing and implementing healthcare IT. Currently, the process for selecting IT is highly fragmented, and organizations rely on data that does not meet public health needs. This leads to increased cost and decreased functionality at the expense of patient care.

Reducing Clinician Burden Through the Use of Health IT

According to the same Stanford poll previously referenced, roughly 70% of primary care clinicians state that despair and burnout are at an all-time high and the current healthcare IT infrastructure contributes to this. [3]

Clinician burden is realized in the amount of time spent on activities that are not direct patient care. Clinicians regularly voice their concerns about administrative burden by describing laborious overdocumentation “note bloat” and poorly structured electronic health record systems, nicknamed “five clicks to crazy.” These inefficient systems harm clinicians and patients alike as more time is spent managing the process of healthcare rather than providing healthcare.

When the technology revolution finally reached healthcare, it was intended to streamline processes and allow clinicians to spend more time with patients. While electronic health records have been demonized as the root of all evil in clinician burnout and medical errors due to missing or erroneous information [7], it is well documented that the same administrative burden occurred in paper-based healthcare administration [8]. Instead of utilizing healthcare IT to transform healthcare, we simply traded the fragmented, broken system of paper for a fragmented, broken system of mouse clicks.

Clinician experience can be improved through the new E/M guidelines that reduce the documentation needed for a patient visit. But there are technological innovations that can increase efficiency, reduce the amount of time spent documenting patient information, and improve health outcomes such as using note dictation and workflow automation principles such as natural language processing, robotics, and, machine learning.

Healthcare presents a complex management task, and workflow automation can streamline repetitive processes, enabling high-quality, safe, secure, and effective patient-centered care. Automation of rote tasks can reduce errors and decision-making burden. This allows clinicians to devote their time to specialized patient care and allows greater engagement for decision support. This requires standards adherence since automation requires repetition, clearly defined variables for modeling and clear roles and responsibilities for actors.

ONC is preparing its policy and development agenda on modern computing and is committed to supporting clinicians through standards and processes, such as workflow automation. To reduce burden for all and produce high-quality healthcare, these processes must preserve the following:

- Measurable goals

- Involvement of stakeholders in design

- Preservation of human judgment

- Avoidance of adverse outcomes

- Scalable approaches across settings

- Incorporation systems for reducing health inequity

- Improved efficiency, savings, and quality

Actionable Data as the Great Equalizer

We need comprehensive, interoperable data to strengthen the nation’s healthcare system, to reduce inequity, and improve health outcomes. This is only possible through a complex fusion network of data and meaningful analytics.

As a healthcare analytics organization, we embrace and drive adoption of standards and technologies that make research and quality improvement accessible and successful. We support the vision of making actionable data the great equalizer through creating fusion networks of registry data that identify improvement opportunities, investigate what is driving outcomes, and promote future forecasting through advanced predictive modeling.

Together, we can create the healthcare system of the future by creating interoperable networks of actionable data.